Quickly approximating Shapley Games

In this blog post, we will talk about some recent advances in algorithms for approximately solving Shapley Games.

What is a Shapley Game?

At an intuitive level, Shapley games capture the idea of extending one-shot 2-player games to be occurring over multiple stages.

Explicitly, Shapley games are played on an underlying state space . At each

, the two players can each choose one of

actions. Based on their choices

and

, the first player receives a reward

(and the second player receives

) and the game moves to state

with probability

. Furthermore, at each time step there is a probability

that the game ends (thus,

). The goal of each player is to maximize their earnings.

These games were introduced by [Shapley’53], where he also proved that when , the Shapley game has a value: that is, this maximum exists.

Furthermore, this value can be characterized as the solution to a specific fixed point equation: defining to be the optimal payoff of a two-player game on the payoff matrix

, the value of a Shapley Game is the unique vector

satisfying

for all

(here,

). Intuitively, this makes sense: a player’s expected payoff at a given state

is determined exactly by their current payoff

and their future payoff

.

We are often interested in the setting where is exponentially small (in fact, it was later proven that Shapley games have a value when

but we will not focus on this case).

Connecting Shapley Games to Fixed Point Theorems

As we talked about above, the value of a Shapley Game is the unique vector satisfying

for all

. If we define

to be the vector consisting of the right hand side over all $\latex v\in V$, then it turns out that in addition to being polynomial-time computable,

actually satisfies two special properties:

- Monotonicity: for every

,

- Contraction: for every

,

- Later, we will also care about defining a contraction property for discrete functions: in this case, we loosen the constraint to be

(else, all values are actually equal)

- Later, we will also care about defining a contraction property for discrete functions: in this case, we loosen the constraint to be

By Tarski’s Fixed Point Theorem, every monotone function has a fixed point; and by Banach’s Fixed Point Theorem, every contracting function also has a fixed point.

For our algorithms, we will not be interested in the exact Shapley value, but just an -approximation of it. To define this, let

and

.

Then, [EPRY’20] constructs a (discrete) monotone contraction such that

- A query to

requires one query to an oracle for

.

- Given any

with

, we can construct in polynomial time an

such that

.

satisfies that

. This last condition is an implementation detail which will make some of the later exposition simpler.

With this reduction in mind, the challenge for approximately solving Shapley Games has just become one of finding monotone/contracting/both fixed points of a function over . In the next few sections, we will talk about some recent algorithms for accomplishing this.

It’s important to note which factors are important for the runtime and query and complexity here: we will often consider and

to be “reasonable” (since this is the size of the state space and the bit complexity of the input, respectively). In a reasonable application, we would expect

to generally be fairly small, likely

.

Complexity Implications

Before describing algorithms for approximately solving Shapley Games, let’s take a look at the complexity landscape surrounding it.

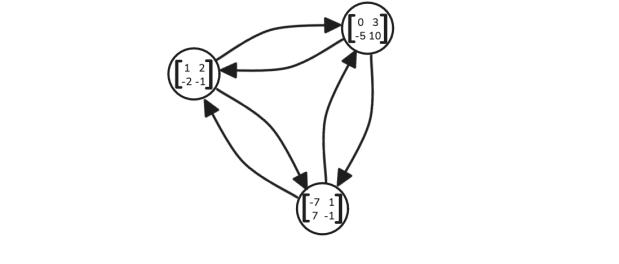

Above is a diagram of the relevant complexity classes surrounding Shapley Games. These are, in order:

- PPAD: A prototypical complete problem for PPAD is End-Of-Line: Given an (exponentially large) directed graph consisting of lines and cycles and a start point of a line, find the end of one of the lines. Two famous examples of problems complete for PPAD are finding (approximate) Nash Equilibria and Brouwer Fixed Points (Given a compact domain

and a continuous function

, find an

such that

).

- PLS (Polynomial Local Search): A prototypical complete problem for PLS is the following: given an (exponentially large) DAG and a potential function

which only decreases along directed edges, find a local optimum. It is believed that neither PLS nor PPAD are subsets of each other.

- CLS (Continuous Local Search): An example complete problem for CLS is Gradient Descent. It is also known that

(shown in [FGHS’22]).

- UEOPL (Unique End of Potential Line): There is a hidden class not in the above diagram: EOPL (End Of Potential Line). This marries the prototypical complete problems for PPAD and PLS by adding a potential function to End-Of-Line. Building on this, UEOPL asks for there to be exactly one line (and hence exactly one solution). By definition, this lies within

.

From first principles, it is true that computing the (approximate) Shapley values lies both within PPAD and PLS (and hence within CLS), by noticing that it is a special case of Brouwer’s Fixed Point Theorem and admits the potential function , respectively. Furthermore, by Shapley’s Theorem, we know that there is a unique solution. Recently, [BFGMS’25] showed that computing approximate Shapley Values is within UEOPL. More generally, they showed that computing a fixed point of any monotone contraction is within UEOPL.

Algorithms

Inefficient Algorithms

Let’s begin by “forgetting” the contracting constraint and just trying to find a fixed point of a monotone . A simple algorithm for this task is to consider the sequence of iterates

. Since

is monotone,

, and

for all

, it follows that there must be a repeat in this sequence. Unfortunately, the query complexity of this algorithm is

. Since we are often interested in the setting where

and

are exponentially small, this is too slow.

In the opposite direction, suppose we just knew that was contracting, and not monotone. In this case, we can find an

-approximate fixed point of

directly by starting at an arbitrary point and considering the sequence

which will require

iterations and is also too slow.

On the other hand, exciting new work by [CLY’24] gave an algorithm with query complexity for the task when

is just contracting. Unfortunately, the runtime of this algorithm depends on factors of at-least

(there is a brute-force grid search over

between each query).

By contrast, in the upcoming algorithms, we will have the property that the “external” runtime is at most some times the query complexity. Here, by external runtime, we mean the work in between oracle calls to

.

We will now describe some algorithms for computing fixed points of monotone contractions. The current state of the art is an algorithm by [BFGMS’25] that takes queries to

to find such a fixed point. Here, we will present a simplified version of this algorithm that takes

queries to find this fixed point.

First Pass: Monotone Fixed Point Algorithms

On the path to faster algorithms, let’s begin with . Here, we know that

and

. We can then binary search for a fixed point, preserving the invariant that

and

at each iteration. This takes

queries to

.

Similarly, we can do a recursive -layer binary search to find a fixed point when

is

-dimensional, which requires

queries to

.

To improve this algorithm, let’s decompose it into two parts: a base case and a gluing theorem.

- The base case here is solving

in

queries.

- The “gluing theorem” says that if we can find a fixed point of a

-dimensional

in time

, then we can find a fixed point of a

-dimensional

in time

.

One road to improving the runtime of this algorithm is to improve the base case. That is, is there some fixed constant where we can find a fixed point of a

-dimensional

in

queries?

Recent work in [BPR’25] has given a lower bound of for all

, and there is a natural

lower bound for

. However, we can do better for

, as shown in [FPS’22]:

Given a monotone

, there is an algorithm which takes

queries and outputs an

for which

.

Immediately, this implies an algorithm taking queries for finding a fixed point of a

-dimensional

. However, this is not the end of the story, as we can also derive a more general gluing theorem, also shown in [FPS’22]:

If we can find fixed points of

dimensional

s in query complexity

respectively, then we can find the fixed point of a

dimensional

in query complexity

.

Together, these imply an algorithm running in time for finding a fixed point.

Gluing Theorem

Let’s begin by discussing a variant of the gluing theorem from [BFGMS’25]. In particular, suppose that we have oracles and

for the

and

dimensional monotone contraction problems, respectively.

As a first pass, consider giving to the function

: in other words, call

on the slice where the first

coordinates are fixed to be

and return the result of calling

on this fixed point. Naively, this seems reasonable:

is guaranteed to return a fixed point and hence when

returns a fixed point in the first

coordinates it must be the case that we know its fixed part in the last

coordinates.

The issue, however is that is not monotone nor contracting: for example, suppose that

was just the identity function: now,

is free to return any point in

on each run. To fix this, we will follow [BFGMS’25] and suppose that, magically,

and

both return the Least Fixed Point (LFP) of their input function (by Tarski’s Theorem, the set of fixed points form a sublattice so there exists an LFP: the meet of all of the fixed points).

Proof

We claim that this is sufficient to force to be a monotone contraction. To prove this, suppose we have two queries

and

, and suppose that

and

. We show the two necessary facts:

- If

, then

.

- It is true that

(we prove this when

, which can then be extended by induction)

To prove the first fact, we claim that for every such that

, there exists a

with

such that

, and that a similar statement holds in reverse (i.e., given a

we can find

with similar properties). The key observation is that

, where the last inequality follows from

.

Thus, we may consider the sequence . Each of these is upper bounded by

and they form an increasing sequence, so one of the values among them must yield a fixed point

. We can do a similar argument in the reverse direction, so this implies that when

we also have

. Furthermore, this also implies that

.

Now, suppose and

are incomparable. Then, compute

(the meet of the two) and

(the join of the two) which satisfy

. It follows that if

and

are the least fixed points for

and

(and, as before,

and

are the fixed points we are looking for), then

and thus

. Hence, we are done.

With this in mind, the final question is: how can we find a Least Fixed Point? If were just monotone, then [EPRY’20] showed that this was NP-Hard. It turns out that when

is

-dimensional, there is a reduction from [BFGMS’25] that gives us the LFP with constantly many extra queries. We now have that the query complexity of gluing the two instances requires

queries to

.

Base Case of [FPS’22]

We will briefly describe the parts of the base case algorithm from [FPS’22] that we will later use to inform our algorithm for monotone contractions.

To describe the base case algorithm, we need the following definition:

Given a function

, we let

and

.

Finding a fixed point is equivalent to finding a point in . With this definition in mind, we can break up the [FPS’22] base case algorithm into two steps:

- For a fixed

, find some vector

with

in

queries.

- Binary search on

to find a fixed point.

Overall we run the first step times which gives the final

number of queries.

Brief Aside: Gluing Up & Down Points

Before discussing the [BFGMS’25] result, it’s worth mentioning that it is also possible to write a gluing theorem which uses just the first step of the above base case: that is, given oracles which compute either an Up or Down point (given a fixed coordinate), glue them together to find either an Up or Down point of a -dimensional instance. This result was shown in [CL’22] and immediately gives an algorithm running in time and queries

.

The Power of Monotone Contractions

We are finally ready to bring everything together to describe our algorithm. The key idea is to strip wasteful work from the above base case. In particular, when we search for an Up or Down point along a particular slice

, we are often redoing similar work (for example, we may have gained some information telling us that there is no Up/Down point in a given region of the grid, so there is no use re-searching there).

We will apply this idea to re-use work from prior iterations, so that the total amortized cost of the binary searches comes out to . In [BFGMS’25], they do this directly on

-dimensional instances. In this overview, we will instead show how to compute a LFP of a

-dimensional monotone contraction in

queries, which, combined with the above gluing theorem, yields the desired query complexity.

We will require two properties to hold for our :

: recall that we have this for free from the [EPRY’20] reduction.

- If

then there exists no other

with

; and similarly for

. Equivalently, each

-dimensional slice of

has a unique fixed point.

- We can achieve this as follows: if

and

, then set

(else, set it to

). We can do the same in the

direction. In this way, a consecutive sequence of fixed points will all move down except for the first instance.

- We can achieve this as follows: if

Since each -dimensional slice of

now has a unique fixed point, let’s define

to be the unique fixed point

for a given

, and similarly define

.

With this in mind, we can plot these functions:

Here, the blue line corresponds to and the red line corresponds to

(we have also increased the bounds so that

hits both the top and bottom edge). In fact, we can also say more: the salmon-colored region is exactly the Up set and the green region is exactly the Down set, and where the two lines meet is the set of fixed points!

Note that both and

have slope at most

in their respective directions, which suggests the following: if

and

, then

, and similarly (but in the opposite direction) for the Down set. The reasoning for this is simply the observation that the distance between the two lines is non-increasing.

From this, we can derive our final algorithm: for a given , conduct a binary search to find either an Up or Down point (we are guaranteed at most one, unless there is a fixed point), but keep track of the interval which contains the whole Up/Down slice along that

value. In future binary searches, reuse this interval (shifted appropriately by

) instead of starting with

. In this way, the total number of queries is

since over the course of the algorithm we do at most two full binary searches (one for Up and one for Down points).

Open Problems

There are a wealth of open problems left here, but we’ll mention two.

- What is the true complexity of computing fixed points of monotone, contracting, and monotone contracting functions? This includes both the query complexity and the runtime, as currently we have a large gap between lower and upper bounds.

- Are there other properties of Shapley Games that allow us to get faster approximate algorithms beyond just using monotonicity and contraction?

Acknowledgements: I would like to thank my quals committee: Nima Anari, Aviad Rubinstein, and Tselil Schramm for the useful feedback on my quals talk and some suggestions on this blog post. I would also like to thank Spencer Compton for valuable comments on this blog post.

References

[BFGMS’25] Batziou, E., Fearnley, J., Gordon, S., Mehta, R., & Savani, R. (2025, June). Monotone Contractions. In Proceedings of the 57th Annual ACM Symposium on Theory of Computing (pp. 507-517).

[BPR’25] Brânzei, S., Phillips, R., & Recker, N. (2025). Tarski Lower Bounds from Multi-Dimensional Herringbones. arXiv preprint arXiv:2502.16679.

[CL’22] Chen, X., & Li, Y. (2022, July). Improved upper bounds for finding tarski fixed points. In Proceedings of the 23rd ACM Conference on Economics and Computation (pp. 1108-1118).

[CLY’24] Chen, X., Li, Y., & Yannakakis, M. (2024, June). Computing a Fixed Point of Contraction Maps in Polynomial Queries. In Proceedings of the 56th Annual ACM Symposium on Theory of Computing (pp. 1364-1373).

[EPRY’20] Etessami, K., Papadimitriou, C., Rubinstein, A., & Yannakakis, M. (2020). Tarski’s Theorem, Supermodular Games, and the Complexity of Equilibria. In 11th Innovations in Theoretical Computer Science Conference (ITCS 2020) (pp. 18-1). Schloss Dagstuhl–Leibniz-Zentrum für Informatik.

[FGHS’22] Fearnley, J., Goldberg, P., Hollender, A., & Savani, R. (2022). The complexity of gradient descent: CLS= PPAD∩ PLS. Journal of the ACM, 70(1), 1-74.

[FPS’22] Fearnley, J., Pálvölgyi, D., & Savani, R. (2022). A faster algorithm for finding Tarski fixed points. ACM Transactions on Algorithms (TALG), 18(3), 1-23.

[Shapley’53] Shapley, L. S. (1953). Stochastic games. Proceedings of the national academy of sciences, 39(10), 1095-1100.

Leave a comment